A wing sail is simply a wing (like an aircraft wing) used as a main sail instead of traditional yardage sail. The new AC-45 boats use them in the America's Cup for example.

Wing sails have a lot of potential advantages:

1) they can generate lift from as little as 8 degrees off the wind--vastly better pointing than a sail.

2) their efficiency of lift generation is constant at all wind headings. This means that they range from 25% more efficient (more thrust) on a beam reach to 400% more efficient when pointing.

3) There is far less heeling, and heeling can be easily controlled with minor changes to the angle of the wing. Essentially, the efficiency of a wing comes from imparting much of the force that would have been lost to heeling into lift instead. Less heeling, more push.

4) Sailing consists simply of rotating the wing to point at 10 degrees off apparent wind. This is easy to find by loosing the sail, letting it settle on the apparent wind, and then sheeting it in 10 degrees. There's literally nothing else to it. You de-power by reducing that angle down to whatever you need, so they are excellent in high winds as long as the wind is constant.

But wing sails have a lot of practical problems:

1) Rigid structures are heavy.

2) Rigid structures can't be reefed. The two options with a Wing sail when over powered is to (a) stall it, but that creates drag that instantly converts to heel and can knock a boat down (the AC45 Cats get knocked down all the time because of this effect), or (b) loose the wing sail and let it flap, which is safe for the boat but can destroy the rigid structure of the wing. Neither option is great.

3) Symmetrical wings (wings where both sides are the same shape, like the daggerboard or rudders on a mac) generate less lift than a typical sail. Wings have to be asymmetrical (like an airplane wing, where the top surface is more curved than the bottom) to have a higher coefficient of lift than a sail. Changing the shape of a wing sail from the port tack to the starboard tack requires a lot of internal mechanism that ads to weight and can break.

The three major engineering problems I've identified are:

1) Mechanism to rotate the wing sail around 360 on a stayed rig. Unstayed rigs are hugely expensive, a maintenance nightmare, and prone to shock loading damage. They're also really heavy. Sailboats have thousands of years of stayed-rig engineering already done and it's cheap, so it would be great to keep it.

2) Mechanism to change the foil shape to the opposite side when tacking. The foil shape has to be perfect or the lift characteristics are gone. Wings are notoriously finicky: a simple crease or ridge can destroy laminar flow and voila, all the reasons for using a wing are gone. This is why sails have persisted for so long: they don't have a "works/doesn't work" failure mode the way a wing does.

3) Mechanism to reef the sail when necessary and for storage/trailering, etc.

So here's what I've come up with:

Imagine an "A-frame" mast, where you've got an aluminum mast extrusion port and starboard, coming to a point above the boat at the center of effort. Essentially, these two masts would be stepped at the location of the chainplates on a Mac, and would meet at a point 30 feet above the deck. The masts are 3" round aluminum (or carbon fiber) tubes, with nothing attached to them. At the pinnacle, a custom piece of hardware joins the two masts and has two halyard blocks attached. The masts need not rotate, they are fixed. Because of their simplicity, the two tube masts weigh the same amount as the current Mac mast assembly.

The A frame mast is stayed with a typical forestay and aft stay. There's nothing else, as the A frame masts serve the function of the sidestays.

There are two wings: Port, and starboard. Each is perfectly shaped for its tack, and the wing never changes shape: You use the port wing on a port tack and you use the starboard wing on a starboard tack. So we have our mechanism for changing the wing shape for tacking by simply changing wings. The problem of 360 degree rotation is also solved: Each wing need only rotate 170 degrees (Irons doesn't matter, downwind is wing-on-wing (literally) to produce the full range of motion, so the foreward and after stays are not problems, and the rotation occurs on the side stays, so they are not a problem.

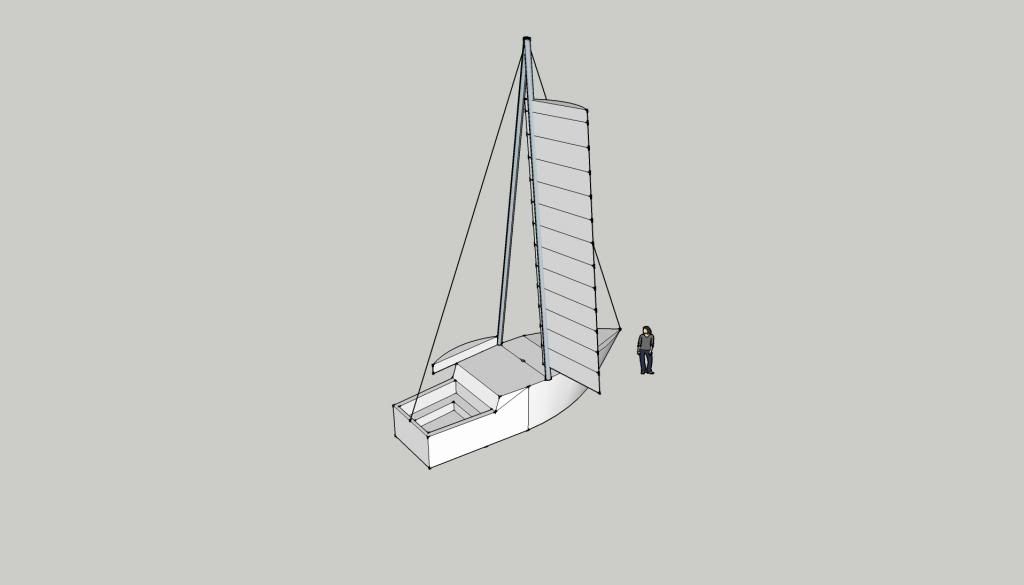

Here’s a 3D perspective view of the rig.

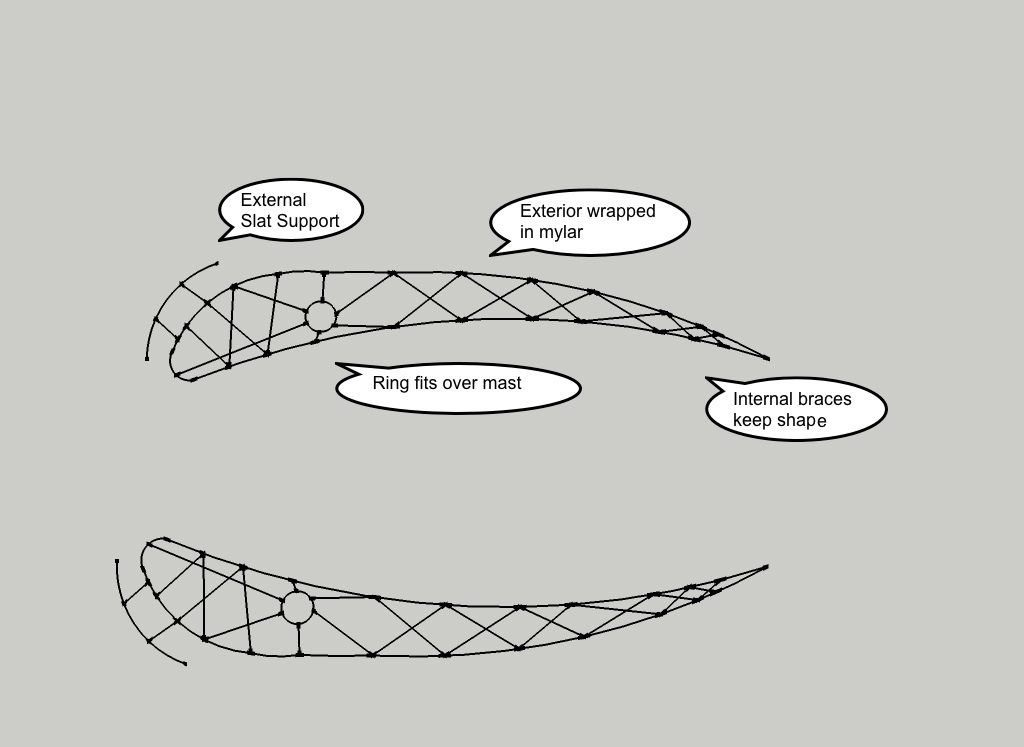

Each wing consists of a "bent teardrop" shaped "wishbone" rib that goes around the aluminum extrusion and forms a 2D section of the wing. This rib includes a ring at the 20% back location that fits around the aluminum mast extrusion, and it is within this ring that the rib slides on the mast. So the masts are simple round tubes, and this rib structure slides up and down it. The ribs also rotate on this interior ring.

A stack of 12 of these ribs are sewn into typical sail mylar like battons at 2' intervals, creating a 28' long wing (there's boom to form the bottom and an external sprit to form the top of the wing), and they collapse down onto the deck around the base of the mast like a sock that has been pushed down. When hoisted, the ribs go up the mast, and when tensioned, the wing becomes rigid: The boom, wishbone ribs, and headsprit provide the shape in two dimensions, and the tensioned mylar provides the shape in the 3rd. In this wing, the boom and headsprit are actually formed by two small tubes fore to aft separated by the mast.

At the leading edge of the ribs, an exterior (outside the mylar) standoff protrudes forward, and another ribbon of mylar is attached to this which goes in front of the leading edge. This is called a slat, and it can dramatically improve the efficiency of the lift generated and increase the "angle of attack", or the range of angles at which the wing will work, up to about 30 degrees. This means a lot less sail handling in confused winds.

Each rib should weigh about 6 lbs. by my calculations, and so the wing structural components will add about 100 lbs. to weight aloft. Given the much reduced heeling, this shouldn't be a problem, but depending on the weight it may be necessary to add a small amount of additional permanent ballast to the boat. 300 lbs. would cover the worst case scenario.

This is a picture of one of the ribs. They’re made of plastic and will likely be 3D printed initially.

So we have our mechanism for reefing: The wingsails reef like a sail with lazy jacks (except that the guides are the mast and the internal ribs). Taking them down is a simple downhaul, and because they slide around the masts, they're controlled all the way down.

To tack, you downhaul the windward wing to the deck, and hoist the leeward wing. In theory, the halyards could be a loop so that as one wing goes up, the other comes down, but in practice you'll want to be able to hoist both wings (for running) or neither (in port) so that's impractical. Because the wing is technically a sprit rig with a head sprit, two halyards are necessary per wing (four total) as well as two downhauls. This does mean that tacking can be a little complicated. However, the dramatic improvement in pointing and downwind performance means that tacking should be far less necessary. 94% of all headings can be reached directly without ever tacking.

Wing rotation is controlled at the boom (bottom sprit) with a leading edge sheet and a trailing edge sheet. Loose both, and allow the wing to come to the wind. haul in the trailing edge sheet (analogous to the mainsheet) until the wing is back ten degrees, and the sail powers up. Cleat it off, then harden up and cleat off the leading edge sheet. A vang is used to downhaul on the boom to keep the sail taut, but it is not necessary to adjust it for sail shape.

The wing will be able to twist a little at the top, which hopefully is okay. Keep in mind that the wing protrudes forward of mast about two feet, so wind pushes there as well, mitigating about half of the twisting force. Also, with a leading edge slat, the sail will generate lift at wind angles from 0 degrees off the wind to about 30 degrees off the wind, which means that the wing can have up to 30 degrees of twist from the bottom to the top without affecting lift performance. You'll notice that bird's wings do exactly this from the wing-root to the tip. So if twist is a problem, the wing can be sheeted in at the boom further to compensate. It's possible that additional controls (such as a top-sprit trailing edge control sheet), structure in the wing (such as a carbon tube along the trailing edge), or a rotating mast mechanism that can rotate the ribs may be necessary, but I don't want to presume those complications until testing shows they're needed. They can all be added experimentally as necessary if the wing tension can't control twist well enough.

No headsail is necessary. A roller-furling 75% jib could be used with the sheets going inside the masts, but there would be little point to it, as wing sails don't suffer from weather helm. This jib would auto-tack as there's nothing in its way. A jib might be useful to create a slat effect, but it might also destroy the aerodynamics and would have to be tested.

A drifter or furling asymmetrical gennaker might be useful for downwind work, but the wing-on-wing configuration of both wings would present more area directly to the wind. A Gennaker would have a better location of effort for kite sailing however, so its probably best to have it.

Each mast and wing is necessarily canted to windward, but this provides an advantage: The mast (and therefore the wing) is less heeled than the boat and so a slight power advantage is obtained (or rather, there is greater righting moment at any particular degree of heel).

Here's a nifty sail power calculator:

http://www.wb-sails.fi/Portals/209338/n ... erCalc.htm

Use this to calculate the kilogram force generated by the standard MacGregor rig, then compare it to the kilogram force generated by the wing foil using the calculator below:

Here's a wing foil lift calculator:

http://www.ajdesigner.com/phpwinglift/w ... _force.php

The values I'm using to calculate lift for the wing sail: Cl=2.5 (conservative), p=1.225 (standard sea level), V=7.7 (15 knot wind), A=18

A coefficient of lift of 2.5 is conservative for a wing foil: Cl as high as 4 can be achieved. At a Cl of 3, a Mac would be sailing at the speed of the apparent wind on any point of sail excepting irons, which would only be 20 degrees wide, even on a Mac. My expectation is that performance would be about double what it is with a typical mac rig.

Trailering is simple: The bases of the two masts are fixed in place, and the wing sails reef down onto these lower sections (right to the deck) when lowered. They form a sail pack about 2’ high. You could call these tabernacles. This is the permanent storage location for the wing sails—they are never removed from the mast base. These tabernacles may be completely verticle, and the A frame may start at the hinge location. I have not decided if there’s any significant advantage to this.

At the 3’ height on each mast there’s a “knee” hinge that allows the A frame to lower FORWARD. They will protrude 10 feet forward of the bow, and 6 feet forward of the trailer hitch, supported at the bow pulpit by an installed crutch. Your option to leave them on and trailer with them extending over the top of the back of your tow vehicle, or take them off at the hinge and store them as per usual. The hinge folds over to keep the sail pack in place if the masts are removed.